Meningitis in Children, Adults – Symptoms, Treatment, Vaccine

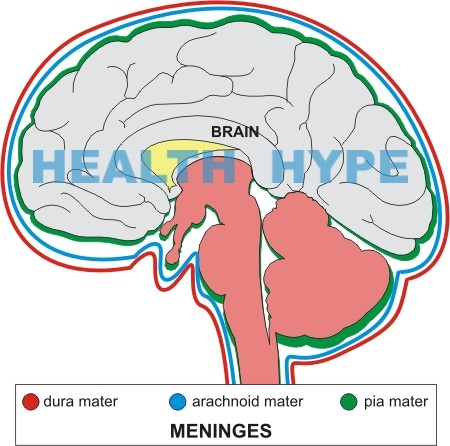

The meninges are membranes that cover and protect the brain and spinal cord. There are 3 layers known as the dura mater, arachnoid mater and pia mater.

- Dura mater is the tough outer membrane. It consists of 2 layers, the periosteal layer lying just beneath the skull and vertebra, and the inner meningeal layer lying towards the brain and spinal cord. The dura is normally attached to the skull or the bones of the vertebral canal.

- Arachnoid mater is the thin, delicate, web-like membrane lying between the dura mater and pia mater. It is normally attached to the dura mater.

- Pia mater is the innermost membrane. It is firmly attached to the surface of the brain and spinal cord.

All the 3 layers are composed of fibrous tissue and a sheet of flat cells which seem to be impermeable to fluid. The arachnoid and pia mater are together known as the leptomeninges.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) fills the ventricles of the brain and the space between the arachnoid and pia mater, known as the subarachnoid space. The potential cavity between the dura mater and arachnoid is known as the subdural space.

What is Meningitis?

Meningitis is the inflammation of the meninges, the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord. It is most commonly caused by bacterial, viral, fungal, or other infections but may also be caused by certain drugs, head or spinal injury, or meningeal infiltration by cancer cells. Meningitis or inflammation of the dura mater is known as pachymeningitis, while that of the arachnoid or pia mater is known as leptomeningitis.

Meningitis is most common in newborns, infants, older children and young adults. Older adults especially at risk are those with a compromised immune system as in those suffering from AIDS or cancer. Symptoms in children may vary from those in adults and absence of specific symptoms in infants often makes diagnosis difficult. Newborns and infants are more often at risk of a severe infection.

Of the different infectious causes, bacterial meningitis is the most severe and extremely contagious. It can rapidly become life-threatening if not treated promptly with appropriate antibiotics. Long-term complications may include permanent neurological deficits such as mental retardation, hearing loss, and cranial nerve palsies. Fortunately, the incidence of meningitis has decreased significantly as a result of immunization programs.

Viral infection is the most common cause of meningitis. Viral meningitis is usually less severe and self-limiting, requiring no specific treatment. The outlook is good, and there are usually no long-term or serious side effects. Viral meningitis occurs mainly in children and young adults.

Pathophysiology

Meningeal irritation may occur in bacterial, viral, and fungal infections, as also in other non-infectious conditions, leading to signs of meningism. The blood-brain barrier normally keeps infection at bay by disallowing harmful organisms such as bacteria and virus from reaching the brain and the meninges via the blood stream. However, in certain circumstances the blood-brain barrier may be compromised and organisms invade the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. The body’s immune system tries to combat this infection by congregation of more white blood cells (WBC) in that area. This causes inflammation of the meninges with resultant edema or swelling of the brain tissue, which may hamper blood flow to vital areas in the brain. Pus formation within the meninges may result in adhesions. These may obstruct the free-flow of CSF and lead to hydrocephalus or may cause damage to the cranial nerves at the base of the brain. There is likely to be a rise in CSF pressure.

Causes and Risk Factors of Meningitis

Meningitis is more likely to cause meningitis in immunosuppressed individuals, diabetics, alcoholics, pregnant women, and in newborns. The causative organisms may be contracted through several possible routes including :

- Air-borne route and through direct contact where it may enter through the nasopharynx.

- Infection can spread directly to the meninges from infected nearby sites, such as from infection in the ear (otitis media) or nasal sinus (sinusitis).

- Infection from distant sites, such as a lung abscess or pneumonia may also reach the brain through the blood stream.

- Direct entry following a head injury or after brain or spinal surgery.

Risk factors may include :

- Overcrowded closed communities, schools, and day centers facilitate easy transmission of infection.

- Antibody deficiency, as in premature newborns.

- Immuno-compromised individuals, such as AIDS patients or those undergoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy for cancer.

Most Frequent Organisms causing Community-Acquired Meningitis

Hemophilus and meningococcal type C infections have decreased in the community due to vaccination against these organisms.

Newborns

- Escherichia coli (E.coli)

- Beta-hemolytic streptococci.

- Listeria monocytogenes

Children <14 Years

- Hemophilus influenzae if <4 years and unvaccinated.

- Neisseria meningitides (meningococcus)

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

- Tuberculosis

Older Children and Adults

- Meningococcus

- Streptococcus pneumonia (pneumococcus).

Elderly and Immunocompromised

- Pneumococcus

- Listeria monocytogenes

- Tuberculosis (TB)

- Gram-negative organisms

- Cryptococcus

Hospital Acquired (Nosocomial) and Post-Traumatic Meningitis

These organisms are often multidrug-resistant.

- Klebsiella pneumoniae

- E coli

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Staphylococcus aureus

Meningitis in Special Situations

- Patients with CSF shunts – Staphylococcus aureus.

- Patients undergoing spinal procedures, such as spinal anesthesia – Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Signs and Symptoms in Adults

The onset is usually rapid, developing over a few hours or within a day or two.

Signs of Meningism (Meningeal Irritation)

- Severe headache.

- Photophobia – sensitivity to light.

- Neck stiffness.

- Opisthotonus – a type of spasm where the head, neck, spine, and heels are arched backwards and the body forms a reverse bow.

- Positive Kernig’s sign – there is pain and resistance on passive extension of the knees with hips fully flexed.

- Positive Brudzinski’s sign – the hips flex automatically flex on bending the head forward.

Signs of Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP)

- Extremely severe headache.

- Vomiting.

- Irritability.

- Drowsiness.

- Seizures.

- Loss of consciousness.

- Coma.

- Irregular respiration.

- Slow pulse rate.

- Hypertension (high blood pressure).

- Papilledema – this is usually a late sign.

Signs of Septicemia

- High fever.

- Malaise.

- Arthritis.

- Odd behavior.

- Rash – may be of any type. Rash is common in viral and meningococcal meningitis. Petechial rash suggests meningococcal meningitis.

- DIC bleeding.

- Increased pulse rate.

- Low blood pressure.

- Tachypnea – increased rate of respiration.

Signs and Symptoms in Children

The characteristic symptoms of headache and neck stiffness may not be present in newborns and infants. Absence of typical signs and symptoms often makes diagnosis difficult. Sometimes the only signs may be unusual crying, poor feeding, or vomiting, especially with a tense fontanelle (soft area on the baby’s head). Vomiting due to gastrointestinal causes is likely to cause sunken fontanelle.

The possibility of meningitis should be kept in mind in newborns and infants with the following signs and symptoms

- High fever, with or without skin rash.

- Irritable, high-pitched cry – the crying may become worse when the baby is picked up.

- Vomiting with tense fontanelle.

- Neck stiffness is usually absent in babies less than 18 months.

- Poor feeding.

- Kernig’s sign positive.

- Brudzinski’s sign positive.

- Opisthotonus.

- Photophobia.

- Drowsiness.

- Lethargy.

- Respiratory distress.

- Odd behavior.

- Arthritis.

- Seizures.

Diagnosis

- Lumbar puncture (LP) is the most important diagnostic test. It should be done immediately unless there are signs of raised ICP such as loss of consciousness, seizures, or severe headache. CSF should be sent for Gram stain, culture, virology, glucose, and protein. Examination of the CSF can indicate the type of meningitis. CSF may be normal in the early stages so a repeat LP may be necessary if the signs and symptoms persist.

- CT scan should be done as soon as possible where LP is contraindicated to rule out a mass or hydrocephalus.

- Blood tests include a complete blood count (CBC), serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine

- Blood cultures should ideally be done before starting antibiotics.

- Blood glucose test to be compared with CSF glucose.

- Urine test includes a routine analysis and culture.

- Stool test.

- Chest x-ray may indicate the focus of infection, such as a lung abscess.

- Nasal swabs.

- Skull x-ray if there is history of head injury.

- Skin scraping of the petechial rash for meningococcus.

Treatment

Viral meningitis is usually self-limiting and does not need any specific treatment. In bacterial meningitis, the choice of antibiotic depends on the infecting organism.

Taking into account factors such as the patient’s age, whether the disease is community or hospital acquired, a known local outbreak of the disease, history of head injury, or if the patient is immuno-compromised, antibiotics may be started empirically against the organism most likely to be involved till test results and antibiotic sensitivity reports are available.

LP, blood culture, and blood glucose are essential for accurate diagnosis but antibiotic treatment should not be delayed if there is suspicion of meningitis but the tests cannot be done immediately. Benzylpenicillin given by intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) injection as soon as possible, sometimes even without waiting for test results, may save a life. Alternatively, ceftriaxone or cefotaxime may be given

General measures may include :

- Protecting the airway.

- Giving high flow oxygen.

- Intravenous access for fluid and antibiotics.

Prevention of Meningococcal Infection

Since meningococcal infection is highly contagious, family members and other close contacts of patients, especially children, should take prophylactic measures for prevention of disease. Rifampicin is usually given for 2 days, adults taking 600 mg twice a day. The dose for children under 1 year is 5 mg/kg 12-hourly, and those over 12 months 10 mg/kg 12-hourly. A single dose of ciprofloxacin 500 mg may be given to adults. The most effective way of preventing meningococcal infection is through vaccination. Vaccines for prevention of disease caused by meningococci Groups A and C are available, but not for Group B.

Vaccine

Vaccination is recommended against some forms of bacterial meningitis, such as :

- Hemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine. Before the 1990s, Hemophilus influenzae type b was the leading cause of bacterial meningitis. Hib vaccine is now given routinely to all children from the age of 2 months as part of routine immunization. As a result, cases of Hib infection and related meningitis have drastically reduced.

This vaccine is also recommended for immunocompromized individuals such as those with AIDS, sickle cell disease, those undergoing treatment for cancer, and those who have had a splenectomy (spleen removal).

- Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine is administered in routine childhood immunization, it is effective in preventing pneumococcal meningitis.

- The two types of vaccines against Neisseria meningitides are meningococcus polysaccharide vaccine (MPV) and meningococcus conjugate vaccines (MCV).

People at higher risk who should have meningococcal vaccination are :

- Routine vaccination with MCV is recommended for all adolescents.

- College freshmen, especially if living in dormitories.

- People who travel to or reside in countries where Neisseria meningitides is common. MCV4 is recommended for people between 2 to 55 years and MPSV4 for those above 55 years.

- Persons with splenectomy or damaged spleen.

- People suffering from AIDS.