Reflux Esophagitis (Acid Irritation of the Esophagus)

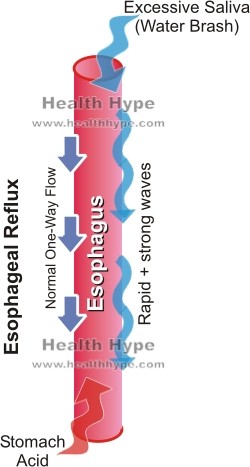

The esophagus is the part of the alimentary tract that connects the throat to the stomach. A bolus of food is propelled down the esophagus and enters the stomach when it pushes past the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). The one-way flow mechanism largely controlled by the LES and mouth-to-anus direction of peristaltic waves ensures that the stomach contents do not spill over into the esophagus. However, this mechanism may sometimes fail to act effectively. Despite the esophagus being developed to withstand mechanical injury, it is not as well suited to chemical insults. Esophageal injury may occur very rapidly if the stomach contents, including its highly corrosive hydrochloric acid, flow backwards up into the esophagus. The subsequent inflammation of the esophageal wall is known as esophagitis or more specifically as reflux esophagitis.

What is reflux esophagitis?

Reflux esophagitis is the inflammation of the esophagus due to the backward flow of the acidic stomach contents. It is known to be the most common cause of esophagitis and is as prevalent as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) which is chronic acid reflux. However, this is not the only type of esophagitis and other causes may be more serious and difficult to treat. Reflux esophagitis is erosive, meaning that the acid ‘eats’ into the layers of the esophageal wall thereby causing open sores (esophageal ulcers). It may predispose a person to infections and may also be a risk factor for the development of a host of complications including esophageal carcinoma (cancer of the esophagus). Reflux esophagitis is more common in adults, particularly those in the 40 plus age group, but reflux occurs in adolescents, children and infants so esophagitis may also affect these age groups as well.

The Esophagus and Acid Protection

The esophagus is just over 25 centimeters (about 10 inches) long and runs from the laryngeal pharynx (throat) to the stomach. It is at times seen as a rather unremarkable part of the alimentary tract as it lacks the digestive and absorptive functions of other parts of the tract. However, the esophagus is significant its own right with the ability to rapidly propel food from the throat to the esophagus, withstand mechanical abrasion from hard and sharp foods and even has its own mechanism to prevent backward flow and ‘flush’ itself should stomach acid spill over into it.

The muscular esophagus is lined by stratified squamous epithelium that contributes to its ability to withstand mechanical abrasion but is easily prone to chemical injury. The lower esophageal sphincter at the terminal end of the esophagus is a circular muscle sphincter that ensures that stomach contents do not spill over. If acidity is detected within the esophagus, the LES contracts tightly. However, in the event of LES dysfunction, this may not provide sufficient protection against the stomach acid.

The copious amounts of mucus secreted by the inner esophageal lining may act as a buffer to the acid to some extent but this is limited in chronic reflux. Other more rapidly acting systems includes the massive secretion of alkaline saliva (water brash) and rapid peristaltic waves aimed to neutralize the acid in the esophagus while forcing the contents back into the stomach.

Despite these rather effective mechanisms in acute settings, the esophagus is not able to maintain these neutralizing functions on an ongoing basis and to a degree that it is entirely spared from from injury. Ultimately the esophageal tissue becomes inflamed (esophagitis) and the esophagus is at risk of further complications in the long term.

Causes of Reflux Esophagitis

Reflux esophagitis is caused by the backward flow of acidic stomach contents into the esophagus. It is therefore a consequence of the same causative factors of that as acute acid reflux and the more chronic GERD. Overall reflux may be due to two factors – reduced LES tone and/or increased abdominal pressure. Various causes may lead to this including :

- Obesity

- Pregnancy

- Alcohol

- Cigarette smoking

- Hiatal hernia

- Medication like CNS depressants

- Delayed gastric emptying

- Diabetes mellitus

- Connective tissue diseases like sclerdoderma

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

The presence of Helicobacter pylori (H.pylori), a bacteria that is frequently implicated in gastritis (stomach inflammation), may have the opposite effect in esophagitis. It is believed that the bacteria’s ability to survive the stomach acid by the ‘cloud’ of ammonia around it may actually reduce the acidity of the acid. This in turn diminishes the extent of chemical injury in the esophagus.

Signs and Symptoms of Reflux Esophagitis

Initially, the signs and symptoms of reflux esophagitis are the same as GERD. However as the condition progresses and ulceration and other complications arise, the clinical presentation may also include these features. Less commonly, reflux esophagitis is asymptomatic for long periods of time until complications arise. This may be seen in silent reflux disease.

- Chronic heartburn – persistent burning pain in the chest

- Nausea

- Regurgitation

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

- Water brash – sudden excess of saliva

- Bitter taste in mouth

Acid reflux may also cause recurrent pharyngitis (sore throat) which is typically worse in the mornings due to a flareup at night and lying down flat when sleeping, exacerbate asthma and contribute to tooth decay.

Other esophageal complications associated with reflux esophagitis may lead to the presence of additional signs and symptoms including :

- Upper GI bleeding

- Hematemesis – vomiting of blood often with ‘coffee grounds’ appearance.

- Melena – dark, tarry stools.

- Esophageal ulcers

- Hematemesis

- Melena

- Weight loss

- Appetite changes – usually loss of appetite

- Esophageal stricture (narrowing)

- Odynophagia – painful swallowing

- Coughing during or after eating

- Weight loss

- Barrett esophagus

- Coughing during or after eating

- Chest pain

- Upper abdominal pain

- Hematemesis

- Melena

Diagnosis of Reflux Esophagitis

An upper GI endoscopy along with a history indicating classical signs and symptoms is usually sufficient for a diagnosis. The esopahgus appears red (hyperemia) and inflamed with ulceration evident in more severe cases. Biopsy may be indicated for nodules which are generally poorly defined and this may reveal hyperplasia or malignant changes.

Treatment of Reflux Esophagitis

Antacids and lifestyle modification (acid reflux diet, weight loss, smoking cessation) may be sufficient for acute cases. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2-receptor blockers are effective both for symptomatic relief and long term management of the condition. Development of complications may require further medical treatment and even surgical intervention.